Book Talk: "Dante and the Mediterranean Comedy"

- Event Type

- Lecture

- Sponsor

- Center for South Asian and Middle Eastern Studies, European Union Center, Medieval Studies

- Date

- Feb 23, 2023 5:00 pm

- Speaker

- Dr. Andrea Celli, Professor of Italian and Mediterranean Studies at the University of Connecticut

- Registration

- Registration

- csames@illinois.edu

- Views

- 27

- Originating Calendar

- European Union Center Events

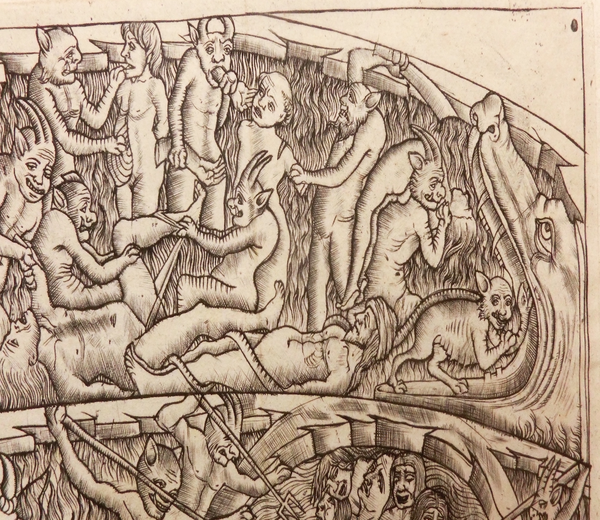

In recent decades studies of medieval literatures have cited the concept of Mediterranean with increasing frequency. And yet, in what sense would Dante’s Divine Comedy be Mediterranean? By virtue of the bounty of references to this sea, its geography and people, its history, its cities, myths, literatures, and religions, through the one hundred cantos? Is it synonymous with Dante’s multilingualism and preference for the vernacular? Or is it linked to the Greek-Arabic sources that inform his cosmology? The definition that this book explores primarily engages with debates sparked by Horden and Purcell’s The Corrupting Sea (2000), in which a few quotes from the poem plays a crucial yet contradictory role. What seems to emerge from the pages of the poem is a vivid yet hardly idyllic image of the Mediterranean world as the unpredictable stage of ancient and contemporary stories of human greed, arrogance, trickery, and violence. If readers were seeking images of the medieval Mediterranean as a space of peaceful trade, intellectual exchange across religious divides, and “convivencia,” they would not find the Comedy a sympathetic source. Indeed, the stern image of the Mediterranean as a sea of corruption and chaos that emerges from the pages of the poem function as an antidote to idealized depictions of it. The first part of Dante and the Mediterranean Comedy analyzes the ideological function of references to the sea in the study of the Comedy undertaken by Enrico Cerulli, a scholar of Somali-Ethiopian languages, and a colonial governor of so-called “Italian East Africa.” The second part presents novel lines of inquiry on the reception and appropriation of the poem, such as the presence of Islamic sources in early commentaries of the Comedyand interclass and cross-religious allusions to Dante’s Hell in graffiti on the walls of the Spanish Inquisition prison in Palermo.